For Unity Day (October 3), which commemorates the re-unification of Germany, we ventured to Berlin, the national capital, by train.

I had the idea to go to Berlin for this occasion, because we wanted to visit there anyway (I hadn’t be there in 20 years; Jeff much more recently), but also because there is so much rich history to explore and participate in there–the Reichstag, the Brandenburg Gate, the remains of the Berlin Wall–all these icons of what it means to be a German, throughout history.

I first went to Berlin as a teenager with my high school, in 1988, when the city was still divided into West (free) and East (Communist bloc), but at the same time, the city itself was an odd oasis surrounded by the oppressive and, to a young American, frightening but intriguing, East German state.

I can remember a long bus ride through gray and depressing East German villages before reaching the Berlin border. GDR officials boarded our bus to check our papers; with their state-issued uniforms, jack boots, and obvious handguns, the intimidation required by a police state was on full display. They also searched the bottom of the bus with mirrors, confirming we were bringing in no contraband (newspapers, currency, food); on our exit the bottom of the bus was checked again to verify we hadn’t tried to smuggle out any humans.

We were accompanied during the entire visit by a state official. Before beginning our guided tour of the sights (such as they were), we were required to change 25 West German Deutschmarks for 25 East German marks, which we were told we must spend, as we were not allowed to leave the GDR with the currency. Since there was basically no economy, we all struggled to spend the money in the shops were were herded into. The money itself was so flimsy it felt like play money from a board game; the coins were aluminum and you could bend them with your hands. Playing along with the game, we purchased a presumably lavish but inedible lunch at a deserted restaurant (placed there for the cause no doubt), but this hardly put a dent in our cash. We went to the saddest department store ever: I remember grey socks, Grandma underwear and long queues. I bought huge boxes of local candy and chocolate to use a gifts (all gross), yet still there was money left. I managed to smuggle out some coins and held on to them for years but sadly have lost track of them.

I was back in Berlin the next summer of 1989 with my friend Audrianna, backpacking around Europe. We didn’t venture into the East that I recall–once was enough! Little did we know the wall would fall that November. That was 30 years ago, this year!

So it seemed only fitting to tour Berlin now all these years later. Walking the streets of the old East Berlin, it’s almost impossible to remember how bleak it was. It turns our one needs a museum to revisit this! I have mixed feelings about the almost romantic notions this engenders; it’s hard to fathom, but there are people still who miss “the good things” about life in the “Democratic” Deutsche Republik (DDR), and I wonder if that’s some kind of survivor guilt? From the outside, there was nothing even remotely “good” except maybe the education system.

So, romanticism aside, I suppose overall, the museum is a good tool to remind people that very quickly–almost overnight in the case of the Berlin Wall–a democracy can become a totalitarian police state, where people become so desperate for even a glimpse of personal freedom or purchasing power, that they are easily coerced into spying on each other; they accept that they cannot speak or move freely, their housing is no longer owned by them, their choice of occupation is not their own, and they are utterly trapped.

Interestingly, in English, when we describe the process of the two Germanys becoming one again, we say “re-unification.” The Germans say “day of unity;” there is no sense of putting it back together, the way it was. I think this is an important distinction, seeing as “the way it was” before was National Socialism; between the wars, a brief democratic Weimar Republic, and before that, an aristocracy. You can read more about Unity Day here.

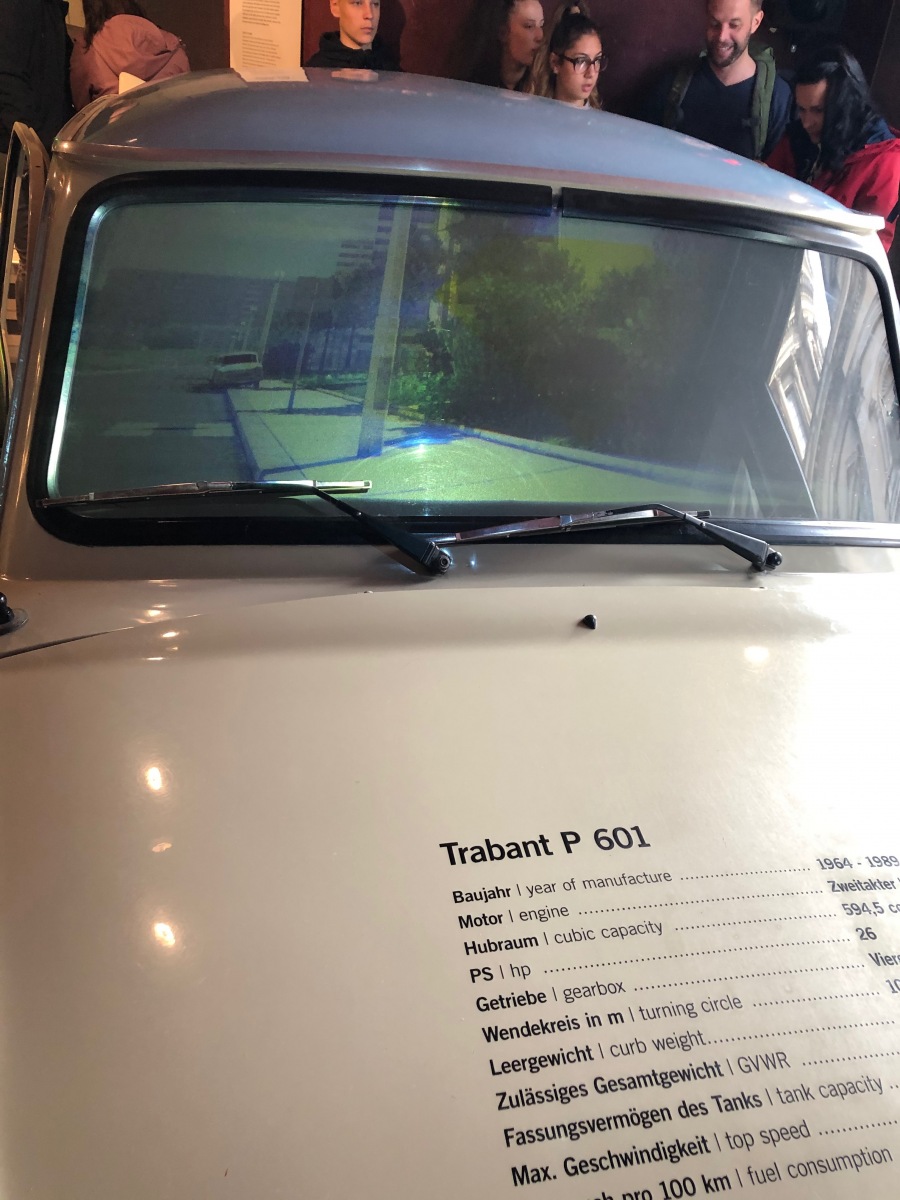

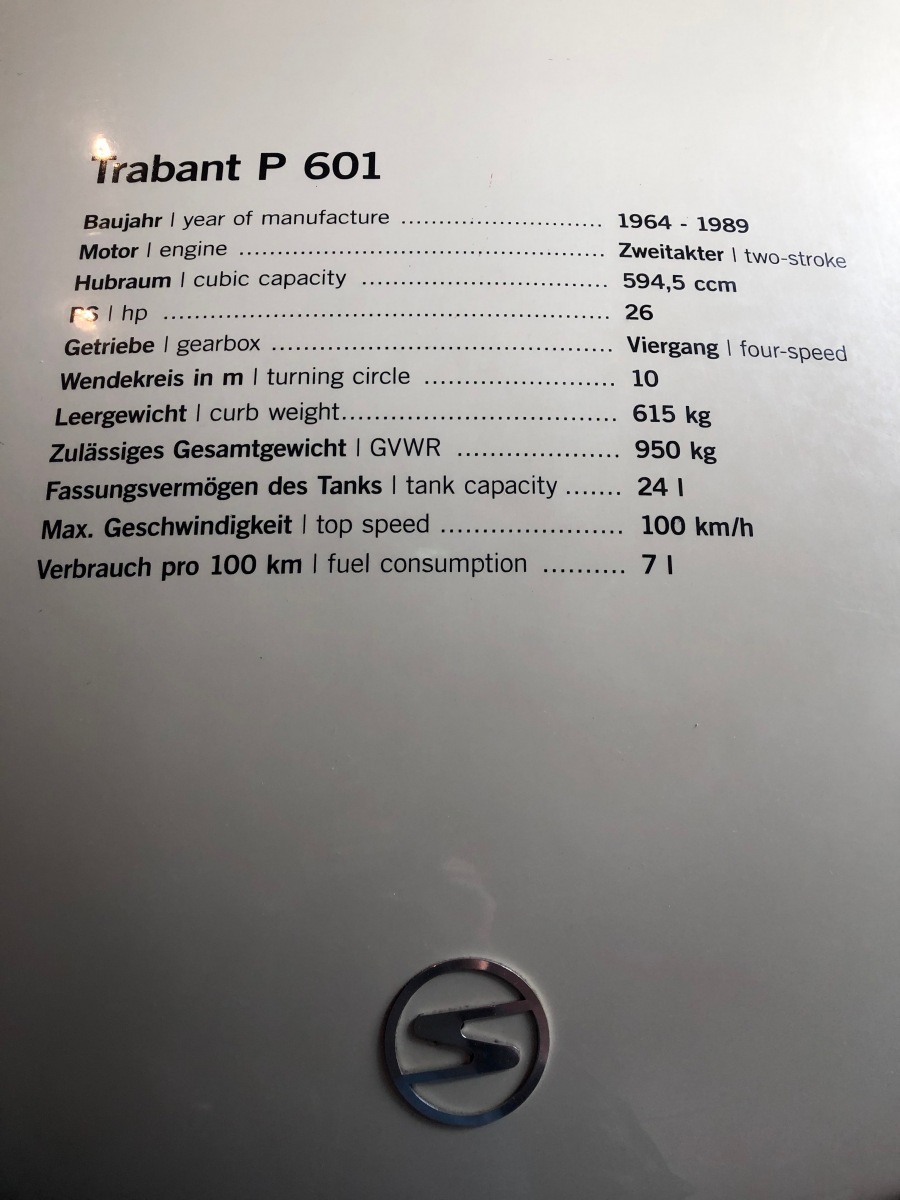

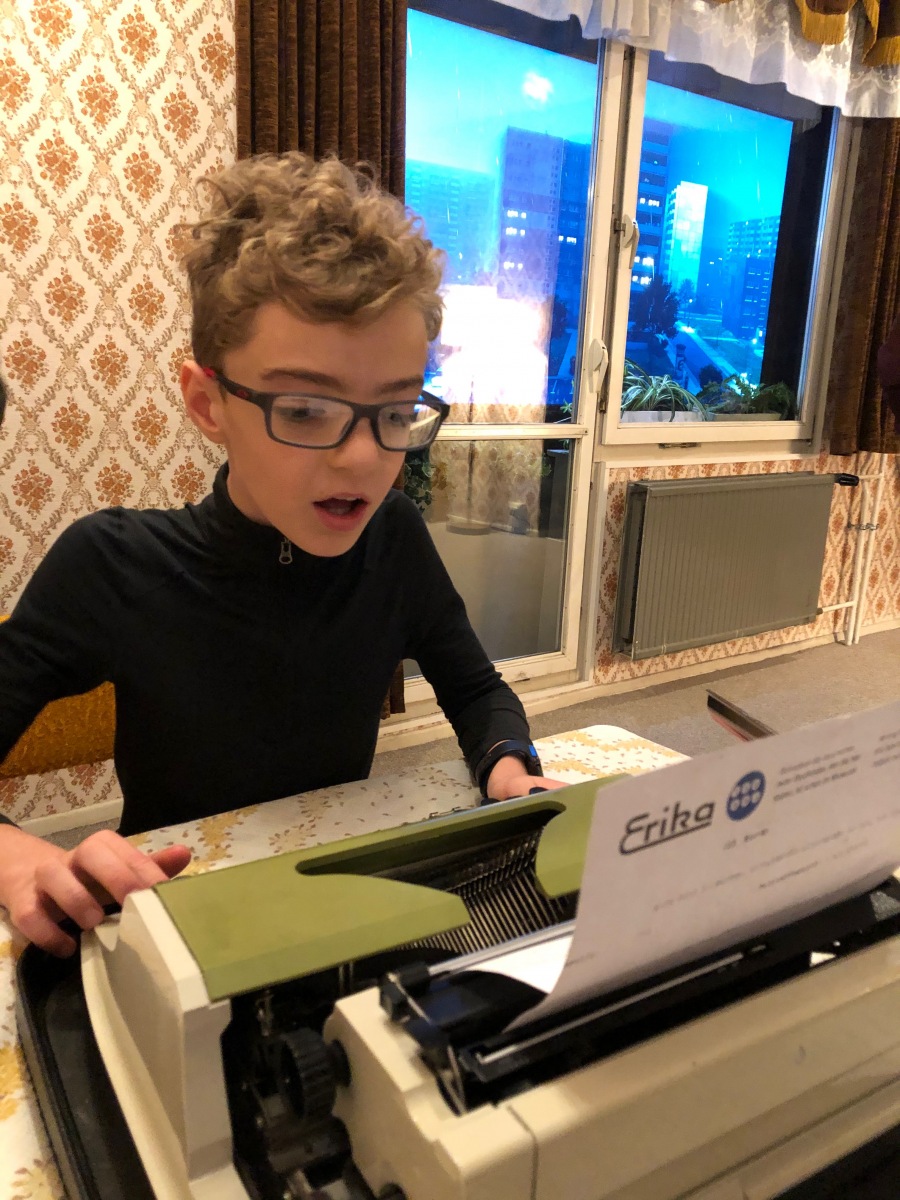

Berlin isn’t a great place to bring kids–it’s very large and spread out with lots and lots of walking, and in general the weather tends to be poor. I tried to break up the history-centered events with things D would like, but I hadn’t planned ahead properly and we weren’t able to do things like walk around the inside of the Reichstag dome, which I know he would have enjoyed. The DDR museum was very interactive and good for him, but also crowded due to the holiday. Still, the virtual reality experience of “driving” an infamous Trabant car was so fun he did it twice. Funny enough, the next day he also sat in a Tesla and pretended to drive. It’s hard to make the mental leap between those 2 worlds!

We also broke up our sightseeing with a trip to an indoor mall (with a slide and that Tesla show room!), played hide and seek in the Muji store, and took a tour of some Berlin sites on a 6-person bicycle! It was a bit odd to cycle by Hitler’s bunker and hear its incredible history while pedaling, but that’s how it is in this city where every block is filled with major events from the 20th century. It seemed everywhere we turned, there’s either a placard or a photo commemorating some fascinating, pivotal, and/or horrifying event.

At our hotel bus stop, the shelter, normally allocated to adverts for things like cigarettes, was instead a permanent poster, marking the building from which Eichmann planned the round up and mass expulsion of Jews from his “Office of Jewish Affairs” on Kurfüstenstrasse (the building is now a hotel–not, thankfully the one we were staying in).

When it comes to the Holocaust, we’ve kept the explanations simple, and brief. It’s not something D can grasp at this age (can one grasp it, at any age?). So. Another day. You will see some photos of us at the Berlin Holocaust Memorial park. In German, this memorial is actually called the Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe, which has obviously a very specific tone, but I did not translate for D. It is an impressive piece of civic art that does an excellent job of making you feel disoriented, less than human, like a rat in a maze, and very, very small. I was quite impressed by D when he observed some kids in the memorial area, playing tag. He said he felt that was inappropriate, so he understand there is a gravity about the subject. I said well, good point. On the other hand, maybe the artist would be glad to see life in such a form, at a place meant to remember death? Who knows. It’s complicated.

Like all children his age, D is quite interested in war–mostly the uniforms, and the guns, and the battles. He knows about how my Grandmother’s brother Ferdinand (“Fred”) was shot down and killed over England just a few weeks into his short time in WWII, and this personal connection is quite intriguing. Since he’d been asking more about the wars, at the school book fair, I picked up The Skylarks’ War , a poetic book about WWI, filled with quirky and memorable characters. It has some very moving passages; reading it aloud gives D the opportunity to enjoy the prose and ask questions. We stop often and talk about geography and other facts.

Reading the book has sparked an interest in visiting war sites, both WWI and WWII, during this year abroad. With this is mind it made sense to visit (west) Berlin’s famous Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, which was bombed during WWII, and the city and church officials elected to not rebuild it, so it could serve as a reminder of the vast damage done to the city (they built a new annex instead). I was delighted that D was interested enough to walk through the exhibit there that outlines the history of the church–this held his interest! Walking with him I learned about the Nazi resistance that was part of life at the church, so we all learned something!

Along with the photos normally post, I have also included a sound recording I made of the church bells of Kaiser Wilhem Memorial Church, calling people to Saturday evening services. Along with the bells, you can hear people laughing and talking on the busy street, bustling along with bulging bags of shopping, heading to restaurants, living their normal, wealthy, peacetime lives, enjoying the long Thanksgiving-like holiday. And yet, as I listen to those bells, it’s hard to not pause, and reflect on all that came before: poppies growing over mass graves in Flanders fields, tanks lining up at Brandenburg gate, endless piles of rubble, even larger piles of belongings from victims of mass extermination, watch towers with snipers, people jumping out of buildings to escape. It’s quite a contrast, and I can’t think of a better way to summarize that strange place called Berlin.

wow. You saw alot! Wonderfully written, felt like I was with you.

You packed a lot into a short time. Listening to the bells as I read your post…feels like I am there with you.

Eric always jokes that you had to order the steering wheel separately from the Trabant – it was considered an ‘option’. Pretty sure that isn’t true but does exemplify the piecemeal way of life the East endured. Eric also says that the very rapid reunification was a shock to the systems of both East and West. The West that had to foot the bill and the East who had to hunt for jobs, insurance, etc – all the things the state had provided for generations. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks for sharing here Eric’s perception of the overly rapid unification. I have read similar articles online; everyone is reflecting on how things are for both West and East, 30 years later. Unemployment for those from the East is still lower and in general people from the East have fewer prospects. It wasn’t just a physical wall but a cultural one that is taking more time than planned to overcome.

Wonderful post. Your description of your early trip was fascinating. Incredible to think of living under those conditions. Truly appreciate your blog.